The end of Moore’s law and the future alternative to traditional computing

-Karthik Ramesh

Why are modern-day computers nearing their limits?

A few years ago, every new generation of processors always offered a pretty significant jump in processing power. Nowadays every successor is akin to its predecessor.

To illustrate the above point, let’s take a look at Moore’s law. The term ‘Law’ seems to grow weaker as the years grow by, but the statement given by Gordon Moore predicts the exponential growth of computing power. Back in 1965, Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, observed that the number of transistors on a one-inch computer chip double every year, while the costs halve.

Now in 2021 the period has been extended by 18 months, and it's getting longer. These increased timescales mean intensive computing applications of the future could be under threat. Back when he proposed this law, he promised if everybody sticks to the law, the future would be a marvelous place to live in and over 50 years his words did come to fruition. But as the periods keep on extending and many companies starting to question the need to stick to the Moore’s law, the future does seem bleak.

Now the reader may ponder on, “Why is this the case?”. Well, I am glad you asked and buckle up because now we investigate the quantum mechanical nature of electrons. Remember the good old days of 11th-12th grade? Of course, you don’t; they are none to remember, over there we solved numerical on the behavior of an electron upon passing a voltage barrier. We used to add up that energy and say the electron has now been excited. But what would happen if the voltage barrier becomes smaller? What would happen if the gap in which the electron was to travel, became thinner? Even thinner than its own radius?

Well to answer these questions we investigate the forms of an electron that is its wave form and its particle form. So even during normal operation of an electron passing through a potential barrier there is always a possibility that the electron would just deflect back on its path because of its particle nature and as we go smaller and smaller the wave nature begins to dominate. When an electron exhibits its wave nature a phenomenon known as quantum tunneling occurs.

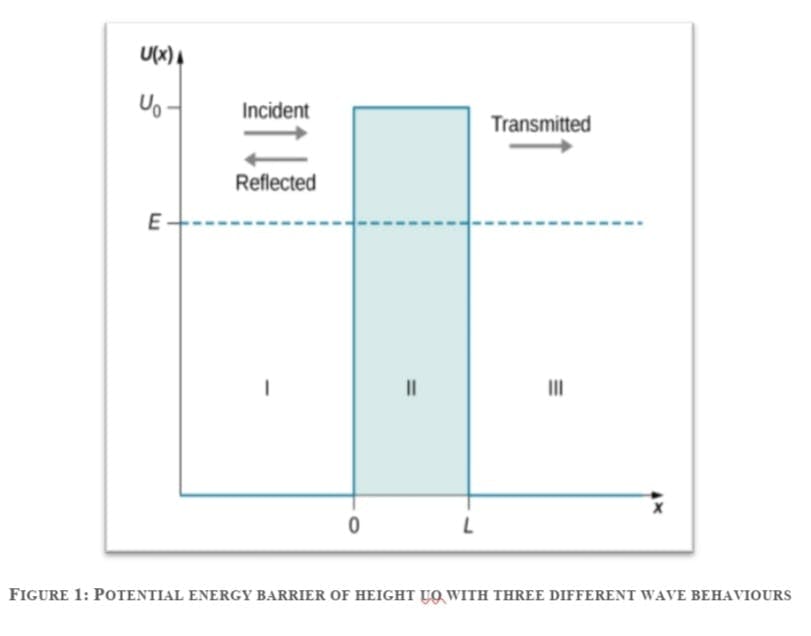

The potential barrier is illustrated in (Figure). When the height Uo of the barrier is infinite, the wave packet representing an incident quantum particle is unable to penetrate it, and the quantum particle bounces back from the barrier boundary, just like a classical particle. When the width L of the barrier is infinite and its height is finite, a part of the wave packet representing an incident quantum particle can filter through the barrier boundary and eventually perish after traveling some distance inside the barrier.

A potential energy barrier of height Uo creates three physical regions with three different wave behaviors. In region I where xL, a wave packet (transmitted particle) that has tunneled through the potential barrier moves as a free particle in potential-free zone. The energy E of the incides a dotted horizontal line at a value less than Uo. The region x less than 0 is labeled as region nt particle is indicated by the horizontal line.

The potential U of x is plotted as a function of x. U is zero for x less than 0 and for x greater than L. It is equal to Uo between x =0 and x=L. The constant energy E is indicated a I and has both incident and reflected waves, going to the right and left respectively. The region between x=0 and x=L is labeled as region II. The region x greater than L is labeled as region III and has only transmitted waves going to the right.

When both the width L and the height Uo are finite, a part of the quantum wave packet incident on one side of the barrier can penetrate the barrier boundary and continue its motion inside the barrier, where it is gradually attenuated on its way to the other side. A part of the incident quantum wave packet eventually emerges on the other side of the barrier in the form of the transmitted wave packet that tunneled through the barrier. How much of the incident wave can tunnel through a barrier depends on the barrier width L and its height Uo, and on the energy E of the quantum particle incident on the barrier. This is the physics of tunneling. This can also be proven using Erwin Schrodinger’s equations of probability distribution.

Modern day transistors keep getting smaller year by year but this in itself poses a challenge for our future. The transistors have three terminals-source, gate and drain and the computer perceives a zero when the gate is blocked and a one when the gate is open, but what to do when an electron refuses to go in due to a very small channel or pops up in awkward places?

As we go on, making smaller transistors to bunch more of them in our modern-day processors, we approach such a future where we can’t go smaller to thereby increase our computation power using our traditional computing techniques.

Then also comes the issue of manufacturing such tiny transistors. At the 32-nanometer transistor scale, you're only talking a handful of dopant phosphorus atoms in the source and the drain. If the ratio gets even slightly out of proportion, the current flow in the channel from source to drain is affected. Getting it right is difficult, and one idea that's consuming a ton of R&D billions is building chips without dopant the altogether. No doping means no counting problem — it's nothing if not lateral thinking.

These new dope-less chips could be skinny layers of silicon with a second gate or vertical layers poking up of out the chip. But whatever these new chip architectures look like, it brings us one step closer to the end of the line for Moore's law in silicon transistors.

Quantum computing: A viable alternative?

When designing complex algorithms and protocols for various information processing tasks, it is very helpful, perhaps essential, to work with some idealized computing model. However, when studying the true limitations of a computing device as mentioned before, it is important not to forget the relationship between computing and physics. Real computing devices are embodied in a larger and often richer physical reality than is represented by the idealized computing model.

Quantum information processing is the result of using the physical reality that quantum theory tells us about for the purposes of performing tasks that were previously thought impossible or infeasible. Devices that perform quantum information processing are known as quantum computers. Quantum computers can be used to solve certain problems more efficiently than can be done with classical computers.

Take a look at some new features present in a quantum computer: -

Qubit:

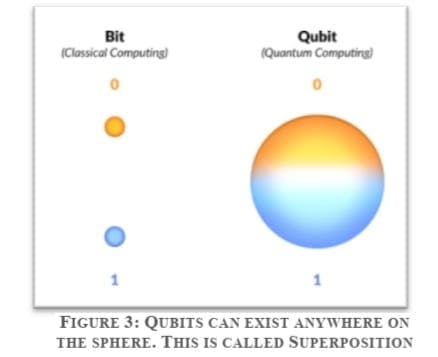

Traditional computers as mentioned previously use 1’s and 0’s to process information and are referred as bits. Over here we refer to such a variable as a ‘Qubit’. Instead of assigning various states of a transistor as a binary variable, quantum computers utilize the spin of an electron. Generally managing and generating this qubit poses a significant thermal challenge. Some companies, such as IBM, Google, and Rigetti Computing, use superconducting circuits cooled to temperatures colder than deep space. Others, like IonQ, trap individual atoms in electromagnetic fields on a silicon chip in ultra-high-vacuum chambers. In both cases, the goal is to isolate the qubits in a controlled quantum state.

The various states of a Qubit:

Superposition

Recall our favorite quantum hero? Of course, its Ant-Man or if you are a DC fanboy its Dr Manhattan. But over here we shall talk about Schrodinger’s cat. Imagine a cat being placed inside a box. Now fill this box with a poisonous gas that has a 50-50 chance of killing the cat. Now, until and unless we open the box, there is no way of knowing whether the cat survives or dies. So, the state of the cat can only known be known if we open the box, i.e., we observe the box. But unless we do that the cat is both simultaneously alive and dead for us due to the uncertainty because of lack of observation.

Another example to grasp this state would be to perform a coin toss. Upon tossing the coin, the result can be either heads or tails and unless and until we observe the coin after it has fallen on the ground, there is no way to know which it is.

You can also make an example out of your future. At the moment all students may or may not get placed during campus interviews but after giving/observing all interviews your future may fall into either one of the two. Sadly, for PDEU students, that won’t be the case as the probabilities for both events are inequal.

The above phenomenon is referred to as superposition. When an object exists in 2 states simultaneously and collapses to 1 state upon observation. To put qubits into superposition, researchers manipulate them using precision lasers or microwave beams.

Thanks to this counterintuitive phenomenon, a quantum computer with several qubits in superposition can crunch through a vast number of potential outcomes simultaneously. The final result of a calculation emerges only once the qubits are measured, which immediately causes their quantum state to “collapse” to either 1 or 0.

Entanglement:

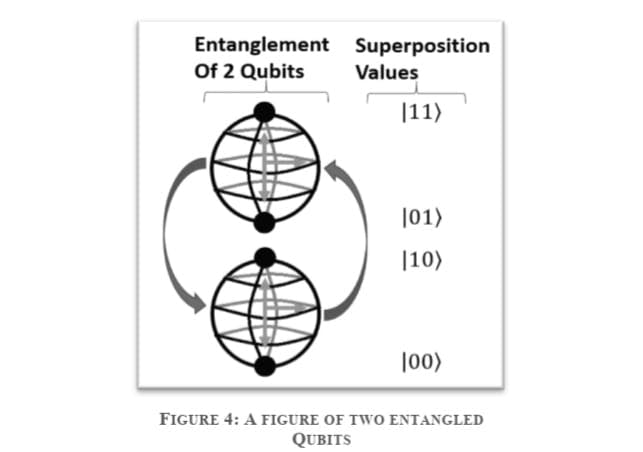

Researchers can generate pairs of qubits that are “entangled,” which means the two members of a pair exist in a single quantum state. Changing the state of one of the qubits will instantaneously change the state of the other one in a predictable way. This happens even if they are separated by very long distances. Nobody really knows quite how or why entanglement works. It even baffled Einstein, who famously described it as “spooky action at a distance.” But it’s key to the power of quantum computers. In a conventional computer, doubling the number of bits doubles its processing power. But thanks to entanglement, adding extra qubits to a quantum machine produces an exponential increase in its number-crunching ability.

Quantum computers harness entangled qubits in a kind of quantum daisy chain to work their magic. The machines’ ability to speed up calculations using specially designed quantum algorithms is why there’s so much buzz about their potential.

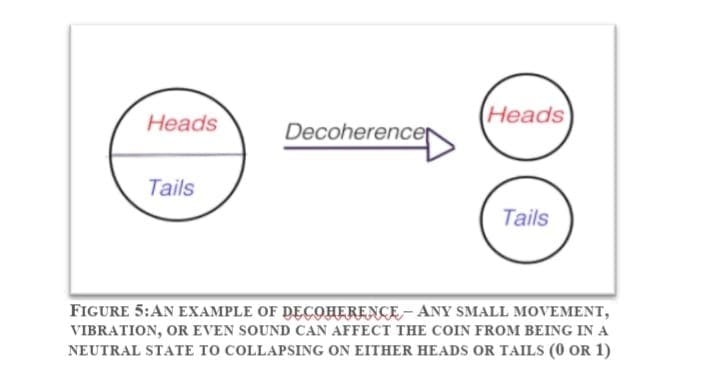

Decoherence:

As already described earlier that managing and generating qubits offers a significant thermal challenge as qubits interact with their environment in ways that cause their quantum behavior to decay and ultimately disappear is called decoherence.

This currently is a major drawback for quantum computers. Qubits are too fragile and even the slightest noise causes decoherence. Smart quantum algorithms can compensate for some of these, and adding more qubits also helps. However, it will likely take thousands of standard qubits to create a single, highly reliable one, known as a “logical” qubit. This will sap a lot of a quantum computer’s computational capacity.

It’s going to be a very long time until Moore’s law totally dies off and the amount of money put into the research and development of Silicone-based transistors will ensure they last for a very long time. Modern supercomputers may satisfy the needs of our scientists and engineers but quantum computing offers domains and venues their minds crave for.